Healing Together: Reducing Mental Health Inequities for BIPOC Families

Healing Together: Reducing Mental Health Inequities for BIPOC Families

Written by Michelle Seymore, National Director of Equity and Partnership at NAA

July is National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month, and The National Center for Adoption Competent Mental Health Services continues to work toward reducing disparities by increasing access to culturally responsive services for families of color experiencing the child welfare system. Mental health is an essential aspect of well-being and continues to be an area where significant disparities exist, particularly among Black, American Indian, and Alaskan Native Communities. These disparities are a public health issue in America recently gaining attention. The disparities are not just numbers on a page; they represent people impacted by systemic inequalities as well as historical and racial trauma. The mental health system is failing to meet the needs of communities of color, and suicide rates are rapidly rising.

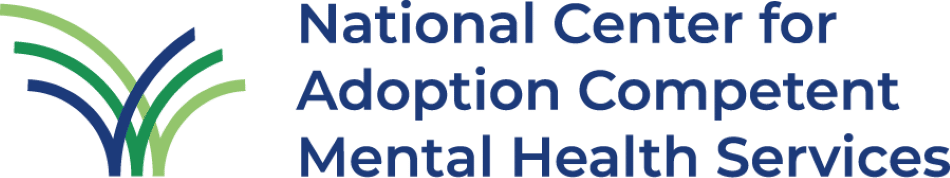

The mental health crisis in Black communities is undeniable when compared to other communities. Between 2011 and 2021, suicide rates among Black Americans increased by 58% according to the CDC. This steep rise is evidence of a growing public health crisis requiring an immediate call to action. In 2020, the third leading cause of death for Black youth between age 15 to 24 was suicide. The suicide attempt rate among Black girls between 14 and 18 years old is highest at 15.2 % compared to 9.4% for White girls in the same age group. These statistics are particularly concerning as these youth represent the BIPOC community’s future.

The overall suicide rate in Black communities is concerning, and there are significant differences between Black males and Black females. Black males are four times more likely to die by suicide than Black females, based on a 2018 statistic. According to a study published in the Journal of Community Health, Black males had a suicide rate of 9.2 per 100,000 individuals, compared to 2.1 per 100,000 for Black females. This data indicates an urgent need for tailored interventions to support the mental health needs of the entire Black family.

American Indian and Alaskan Native children and adolescents have the highest rates of major depressive episodes and self-reported depression compared to other racial and ethnic groups. These high levels of depression resulted in suicide being the leading cause of death for American Indian and Alaskan Native girls between the ages of 10 and 14 in 2014. American Indian and Alaskan Native females were four times more likely than white females between the ages of 15 and 19 to commit suicide. This crisis is exacerbated by co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse being almost three times higher than the general population.

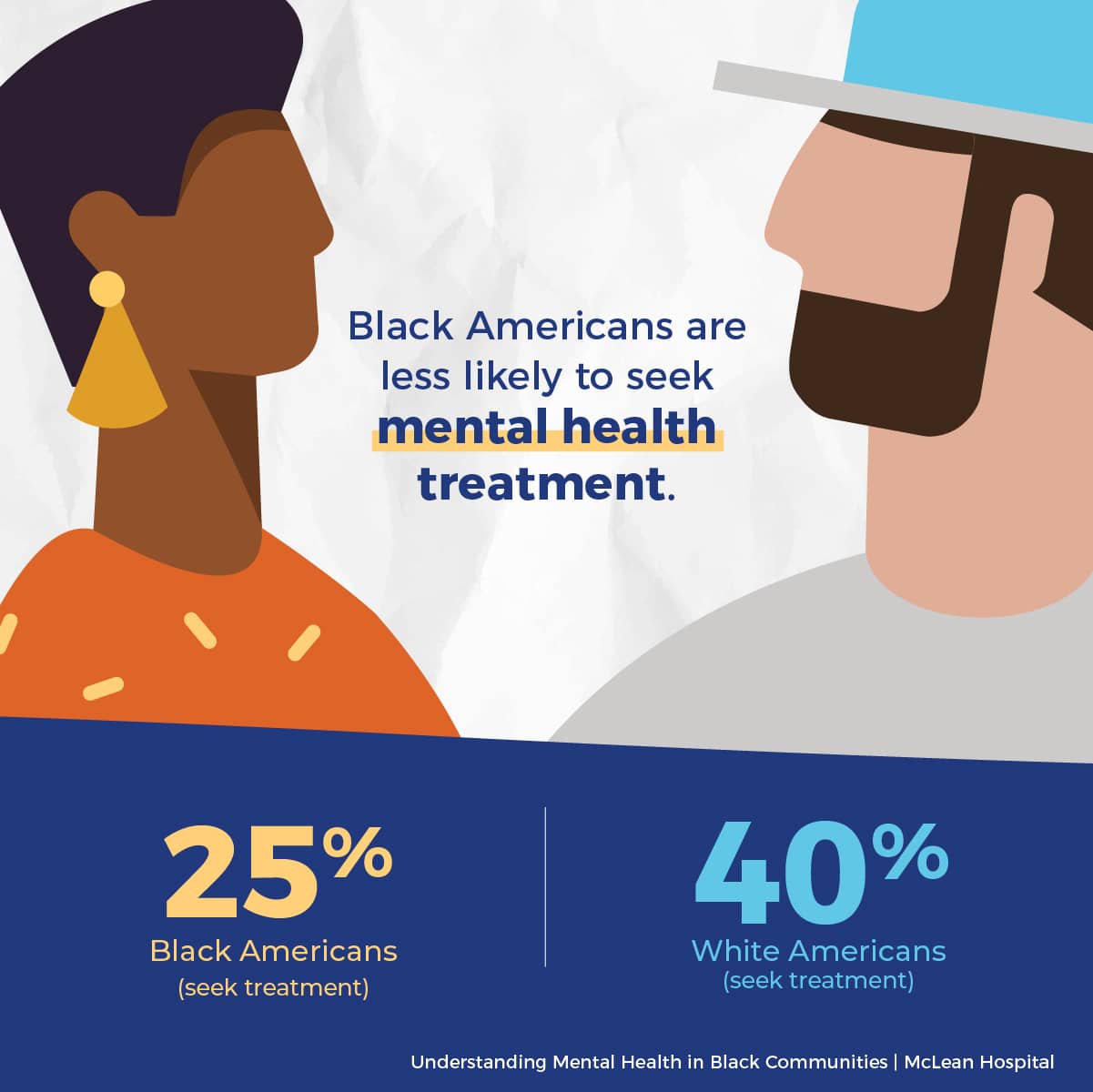

Addressing this crisis is complicated; communities of color are less likely to seek help for mental health concerns than their white counterparts. McClean Hospital reports that approximately 25% of Black people seek mental health treatment, compared to 40% of White people. Black parents seek mental health services at a lower rate for their children as well.

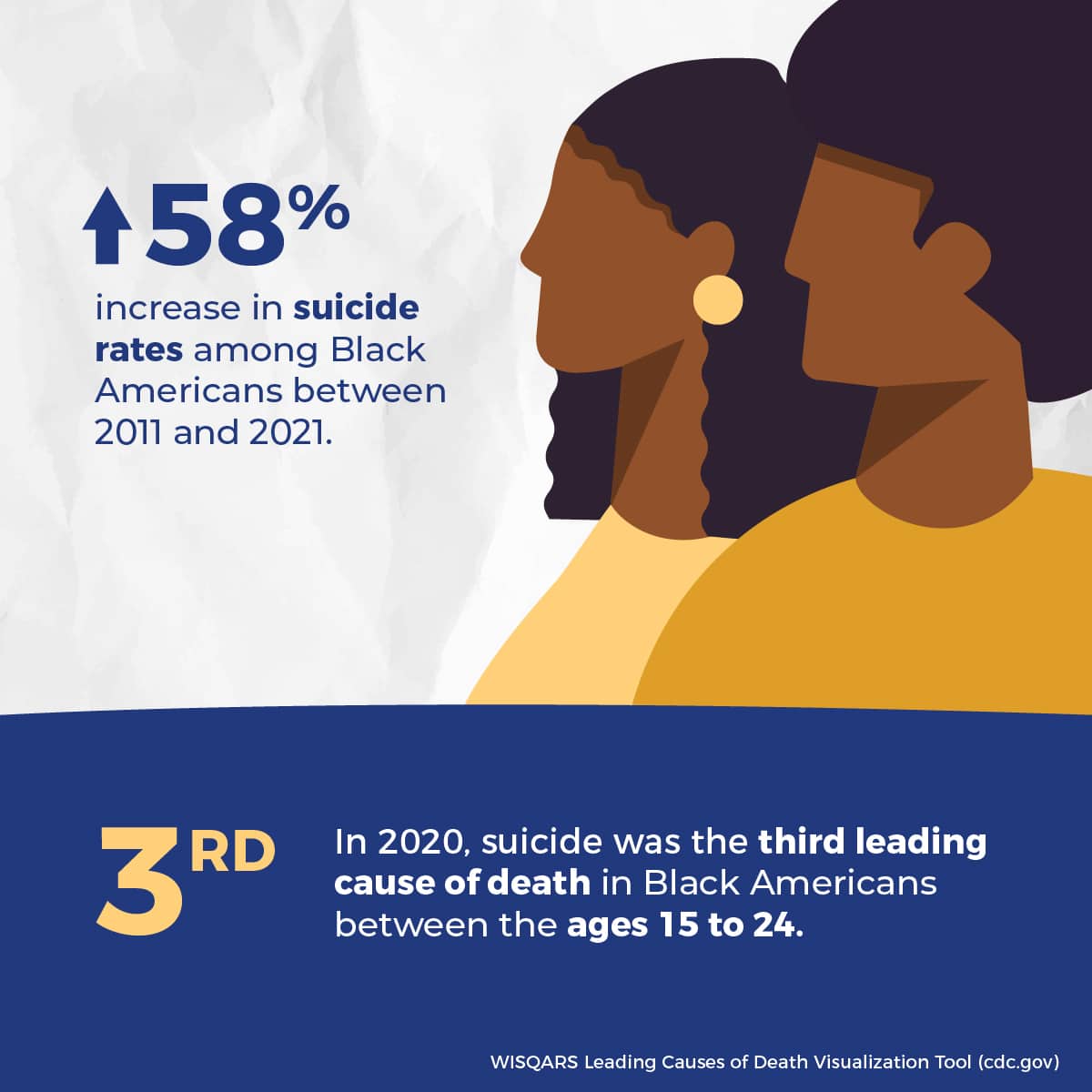

Hispanic, American Indian and Alaskan Native communities have experienced systemic racism and racialized trauma, cultural stigma, and lack of representation in systems of care that contribute to the underutilization of mental health services. Research reports fewer Latino children (8 percent) than white children (14 percent) have ever received mental health services.

Black, American Indian, and Alaskan Native people report elevated levels of stressors associated with systemic racism and racialized trauma. Housing, health care, education, and employment inequities result in communities of color disproportionately experiencing stressors that are significant indicators of mental health issues. Specifically, exposure to violence in the community or with law enforcement leads to chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The mental health of parents impacts the mental health of their children through various pathways. Genetics, community resources, parenting practices, and economics contribute to children’s mental health and well-being. When parents do not have the information, education, and access to resources to address their mental health issues, it impacts the well-being of the entire family unit, often over many generations. Protective factors and interventions can help improve mental health outcomes for parents and children.

Cultural stigmas about mental health in Black, American Indian, and Alaskan Native communities result in youth being under or misdiagnosed, having delayed interventions, and developing a negative self-perception. Survival, weathering the storm, and enduring or silent suffering are solid or noble attributes in these communities. At the same time, mental health issues are a sign of weakness or a failing. These stigmas can keep parents from asking for help or even talking about their experience, leading to isolation, and worsening of symptoms over time.

Families of color are underrepresented in mental health systems and overrepresented in mandated interventions such as child protection. Black, American Indian, and Alaskan Native children are twice as likely to be removed from their homes compared to white children and have more extended stays in foster care and lower reunification rates. The National Center recognizes children involved with the child welfare system face increased mental health needs. Often, family service plans require participation in mental health services that are unavailable or do not meet the families’ cultural needs.

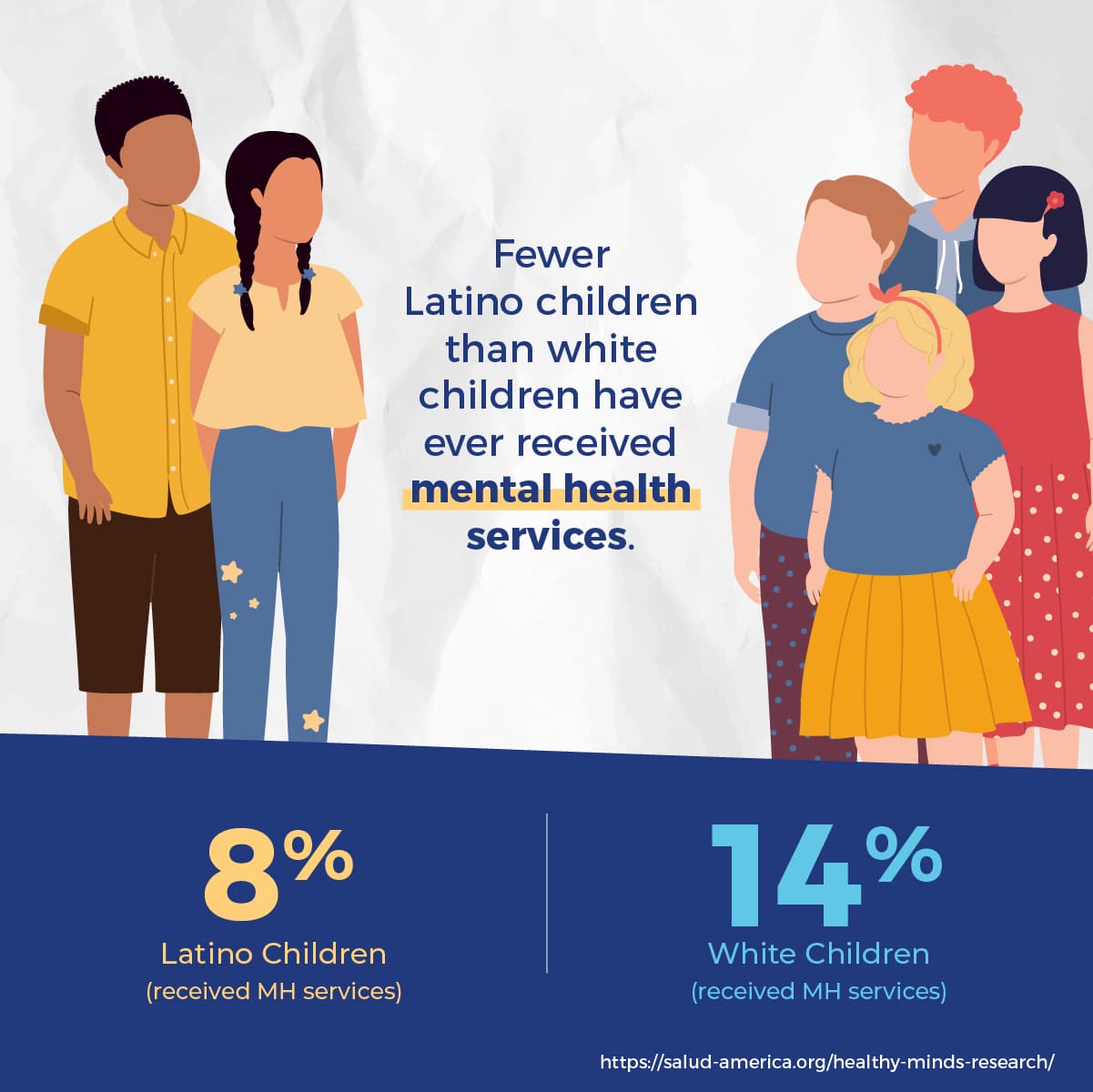

American Indian and Alaskan Native reservations or other indigenous communities have limited access to culturally competent services. Research corroborates a severe shortage of American Indian and Alaskan Native psychologists, an estimate of less than 200, with a dozen or so new degrees annually. Black mental health professionals are underrepresented in the field as well. According to the APA, Of the psychiatrists in the United States, only about 5% of psychologists are Black. Nearly 8% are reported to be Hispanic, 3.28% Asian, 0.13% American Indian or Alaska Native, 0.03% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 2% are people of other racial or ethnic groups. The Black, American Indian, and Alaskan Native lack of representation contributes to mistrust, misdiagnosis, and ineffective treatment plans. Black patients often feel that white therapists or psychiatrists cannot relate to the challenges they face; representation matters.

Creating an inclusive mental health system will require increasing representation, enhancing cultural competence, and providing community education and outreach. Supporting professionals of color in mental health should include targeted recruitment, scholarships, and mentoring programs. Cultural competence and an understanding of the impact of systemic racism on mental health are essential to empowering families of color in their healing journey.

The National Center aims to increase accessibility to child welfare competent mental health services that are culturally responsive and inclusive for all families. As statistics listed earlier show, addressing the mental health needs of Black, American Indian, and Alaskan Native families is a pressing issue that demands immediate and sustained action. By fostering open dialogue, reducing stigma, and ensuring access to culturally competent care, we can create an environment where children of color feel understood, supported, and empowered to seek help. The National Center will work alongside child welfare and mental health systems to develop cross-system collaborations that support the next generation.